What the EU’s 2028–2034 Budget Means for Countries on the Edge of Accession

On July 16, the European Commission released its proposal for the next Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) for 2028–2034 — described as a “dynamic EU budget for the priorities of the future.” The new architecture consolidates spending into four main headings, prominently featuring a new integrated fund combining Cohesion Policy, the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), and other instruments under a single envelope. The budget, proposes the National and Regional Partnership (NRP) Plans to be the primary implementation mechanism, replacing hundreds of operational programmes with just 27 national plans and one Interreg plan.

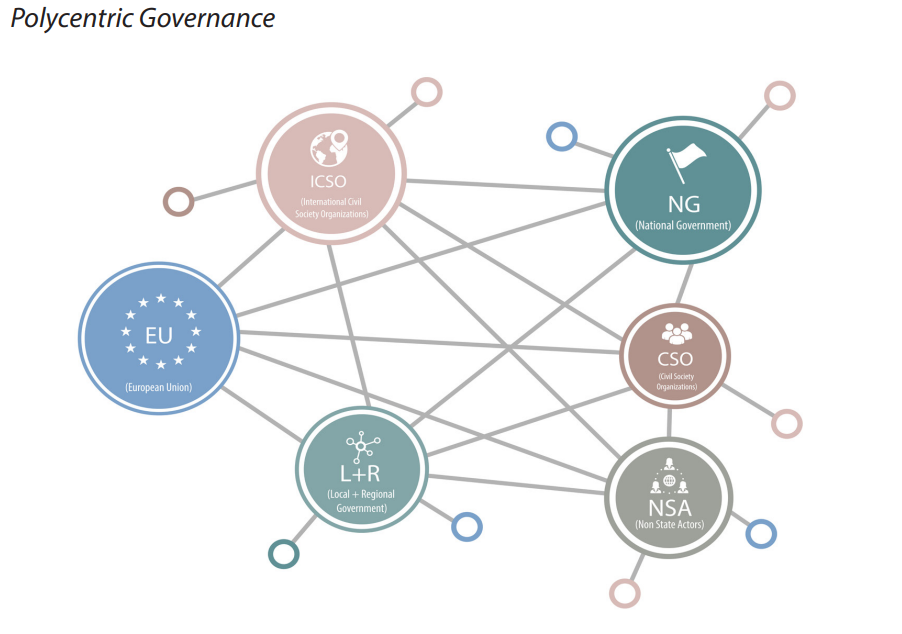

While the Commission frames this as a modernisation effort, critiques have swiftly emerged. As one of our most distinguished colleagues, Kai Böhme, argues in his recent post : the proposal risks reducing cohesion to a compliance tool rather than an inclusive, participatory policy. The simplification of programme architecture may come at the cost of marginalizing regional and local actors, leaving subnational governments dependent on national administrations to define priorities. Similarly, Andrés Rodríguez-Pose and other cohesion experts warn of a deeper erosion: Cohesion Policy as a standalone, democratic instrument may be nearing its end, replaced by a top-down, performance-based logic with fewer safeguards for territorial equity. This comes despite the fact that, in 2024, the future of Cohesion Policy was the subject of extensive reflection by the High-Level Group — culminating in a set of strategic recommendations advocating for a place-based, inclusive and participatory cohesion approach. Disappointingly, few of these findings appear to have been meaningfully reflected in the current budget proposal.

But what does this have to do with Albania?

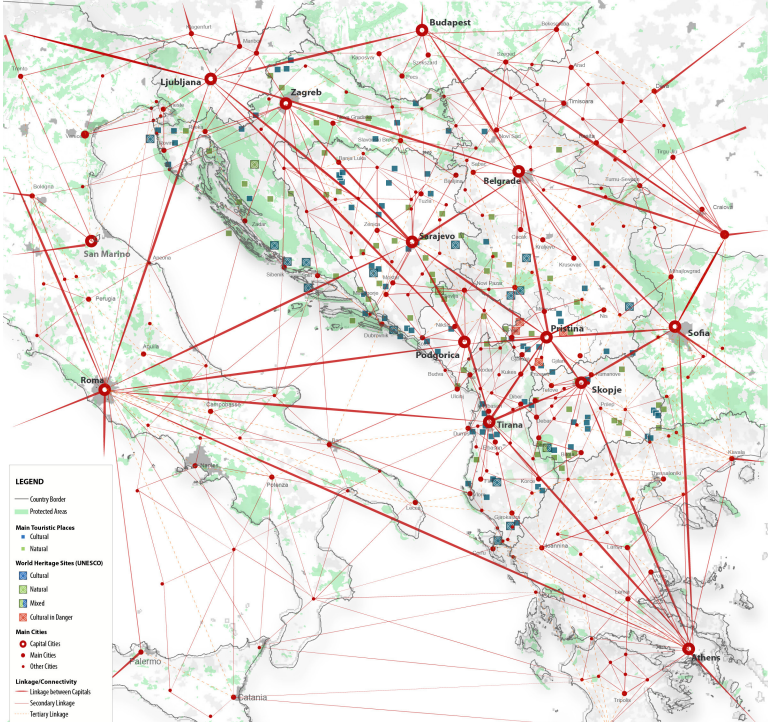

From a territorial development perspective, this marks a significant shift — and one that deserves particular attention from countries on the edge of EU accession, here not only Albania; but North Macedonia, Montenegro, and even Serbia.These countries have long struggled (and still failing) to build the institutional capacities and governance frameworks necessary for effective cohesion-type interventions. The move toward more centralised, performance-based funding mechanisms — tied to reform milestones and broader geopolitical goals — raises serious concerns about their ability to access and manage such funds equitably.

Moreover, the disparities within these Western Balkan countries remain high. Socio-economic divides between urban centers and peripheral/rural regions, underdeveloped rural infrastructure, weak multi-level governance, and limited stakeholder engagement capacity continue to pose serious challenges. Hence the risk remains that, in this new budget logic, these countries and regions may be further marginalised — either unable to compete for resources or forced to comply with reform agendas that do not reflect their developmental needs, nor their endogenous potentials. So, what happened to the place-based development? Or the genuine territorial lens?

As in Co-PLAN we’re diving into the new Disparity Analysis for Albania, we’ll take a closer look at what these new developments entail. Any thoughts to share? Please do comment or e-mail us!